In a new study, researchers from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital have improved chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell (CAR-T) therapy. Their new simplified method selects a favorable T-cell type and shows promise in the laboratory against relapsed T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). The results of the study were published online on August 1, 2022 in the journal Blood with the title “Engineering Naturally Occurring CD7 Negative T Cells for the Immunotherapy of Hematological Malignancies”.

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood cancer, and advances in therapy have improved treatment outcomes. At St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the five-year survival rate for ALL is 94%. However, the prognosis for patients with relapsed T-ALL is poor, with a five-year survival rate of less than 10%.

“Current treatments for T-ALL are still highly toxic,” said Paulina Velasquez, MD, PhD, of the Division of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cell Therapy at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, corresponding author of the paper. “And if T-ALL recurs, the treatment for it will change. It’s challenging. That’s why we’re interested in exploring cell therapies like CAR-T cells.”

Using CAR-T cells to treat T-ALL is a promising approach

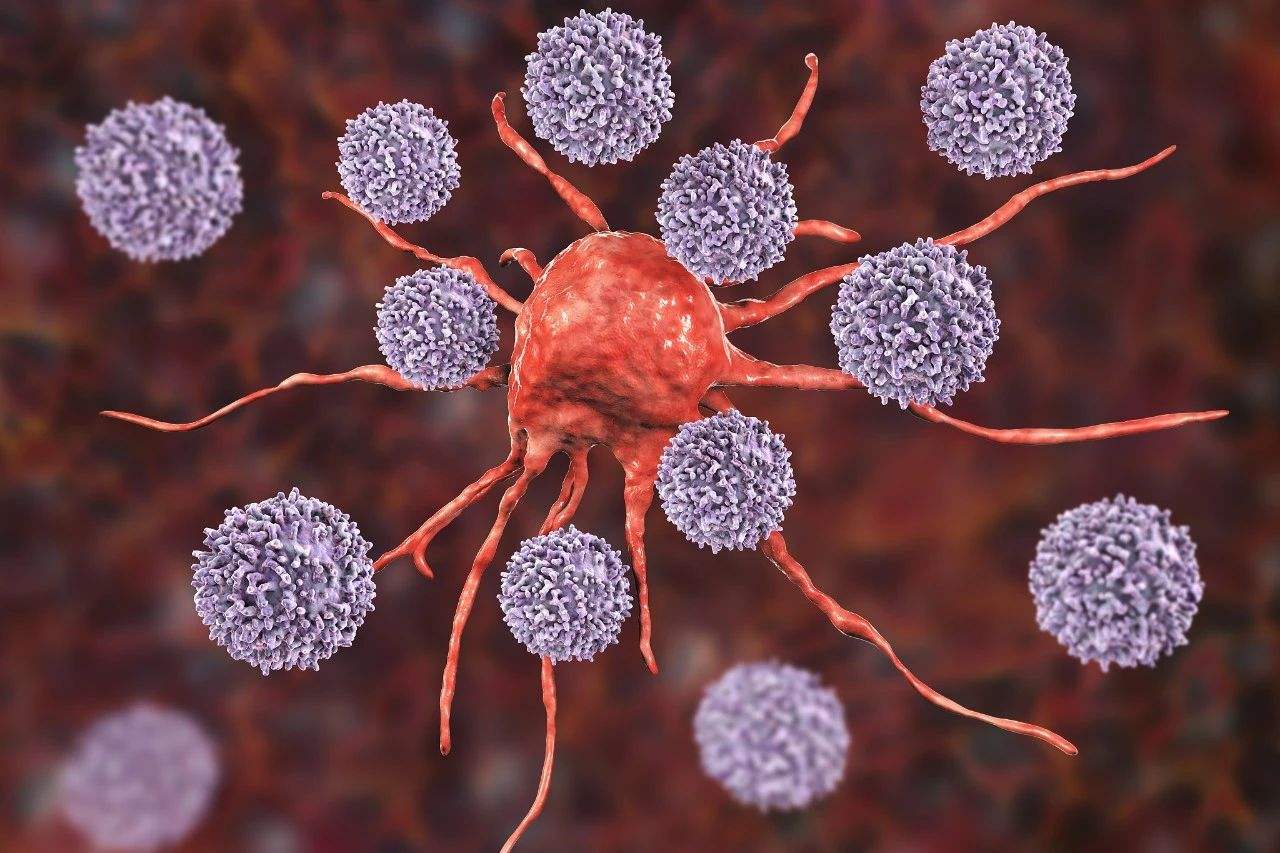

As a type of immunotherapy, CAR-T cell therapy is obtained by genetically modifying human immune cells (T cells) to kill cancer cells. CAR-T cells target a specific protein (called an antigen) on the surface of cancer cells.

“Think of antigens as colored flags displayed by cells,” said co-first author Jaquelyn Zoine, a postdoctoral researcher at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. CAR-T cells can be likened to being hired to find and destroy cells with flags (antigens) of a certain color. The samurai of the enemy (cells).”

Several CAR-T cell therapies for relapsed T-ALL target the antigen CD7. This antigen is present on the surface of many T-ALL cancer cells, just like these cancer cells wave the same flag. However, there is a problem.

“Most normal T cells also express CD7, and because these CAR-T cell warriors are completely on command,” said Abdullah Freiwan, co-first author of the paper, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. “They kill anyone who carries this particular marker. cells, even if it means killing each other.”

Other scientists have tried to address this problem by genetically modifying or otherwise altering CAR-T cells to remove CD7 expression. However, these methods are complex and have associated risks.

Making the most of a small T cell population

These authors focused on a small group of T cells that do not naturally express CD7. They developed a way to select and expand these cells, then make them into CAR-T cells.

In laboratory studies, these CAR-T cells, which do not express CD7, performed very well, effectively eliminating tumors. The cells also provided long-term protection in mouse models of cancer recurrence (rechallenge).

Presence of CD7-free CAR-T cells in clinical trial samples

Based on their preclinical results, these authors wondered whether CD7-free CAR-T cells (CD7-negative CAR-T cells) were present in the blood of patients receiving CAR-T cell therapy. They analyzed data from an unrelated clinical trial of CAR-T cell therapy conducted at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Patients who responded to this cell therapy had a higher proportion of CAR-T cells with low CD7 expression than non-responders.

Velasquez said, “We are selecting this specialized population of T cells that have strong and durable antitumor activity when expressing the CAR. Based on our results, we are considering future clinical trials in patients with CD7-positive T-ALL.”